Jews in Transylvania

In the 19th century, the Israelite population of Hungary and Transylvania grew massively. In 1869, 105,000 Israelites lived in what is now Transylvania, and 542,000 in the whole of Hungary, and their share in the total population increased to 4 percent. By the turn of the century, their number had increased to nearly 180,000 in Transylvania. Parallel to this, an increasing proportion of Jews, previously living in predominantly rural areas, migrated to the cities, which had previously been forbidden for them. By 1910, 44 percent of Transylvanian Jews were living in towns and cities, and by 1930 this proportion had risen to 58 percent. By the eve of the First World War, 70-73 percent of Transylvanian Jews had become native Hungarian speakers and the Yiddish language spoken until then lost ground. In addition, many Jews Hungarianised their names and even converted to Christianity.

The annexation of Transylvania to Romania led to profound changes within Jewish society. Between the two world wars, a significant part of Transylvanian Jewry gradually dissimilated from the Hungarian population for a number of reasons. Antisemitism was one of the most important causes, but the gradual disengagement from was also fuelled by events in Hungary, This included the anti-Jewish violence of 1919-1920; the numerus clausus act, which restricted the number of Jews in higher education (1920); the gradual rightward shift of the Hungarian political leadership in the early 1930s; and then the anti-Jewish laws starting from 1938. Nor did Romanian state pressure favour the survival of the Hungarian identity.

Alongside the Zionist movement, which was gaining more and more adherents, the number of those who considered themselves Hungarian remained significant. Many large entrepreneurs and businessmen of Jewish origin played an active role in the financial support of minority Hungarian cultural and social organisations.

Postcard from Szatmárnémeti (Satu Mare). The town was re-annexed from Romania to Hungary in 1940. The postcard depicts Hungarian head of state Miklós Horthy and the tagline “Szatmárnémeti has returned!” (i.e. to Hungary) (Source: szatmar.us)

For the Jews of Northern Transylvania, the Hungarian administration that replaced twenty-two years of Romanian rule in August-September 1940 meant not only a return to the desired Hungarian state framework, but also a gradual path to disenfranchisement (Jewish laws) and then extermination. The first step in this process was so-called Kamenets Podolsk massacres, which affected thousands of Jews in northern Transylvania.

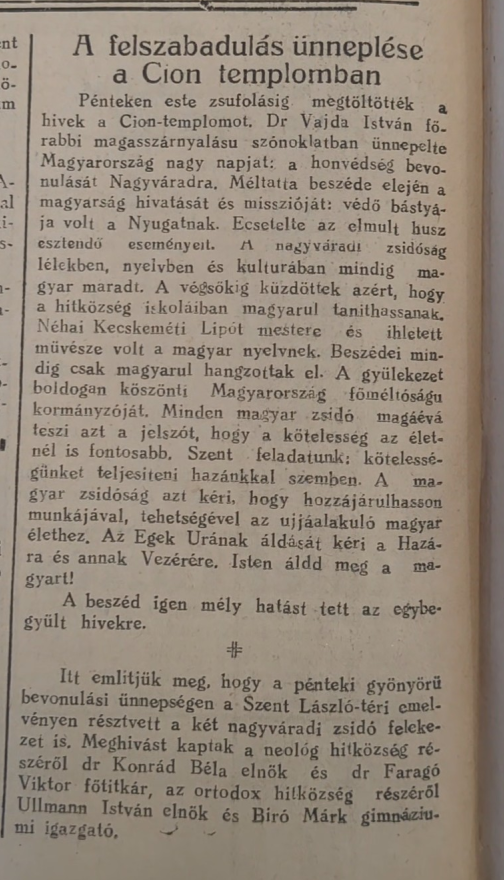

Newspaper article about the Neolog (reformed) Jews in Nagyvárad (Oradea) celebrating the re-annexation of Transylvania to Hungary. Nagyvárad, 8 September 1940.

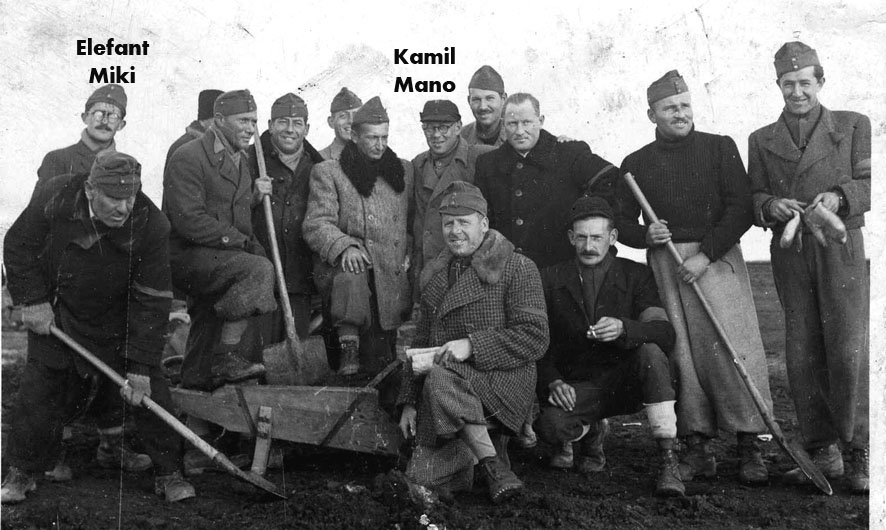

The consequences of the antisemitic measures were exacerbated by the fact that the Jewish intellectual elite suffered significant losses from 1942/43 onwards. This was due to the so-called labour service (munkaszolgálat) i.e. the obligation of Jewish men to serve in unarmed forced labour units in the Hungarian army. After 1942, some 15,000 Jewish men from Northern Transylvania were called up. The majority of the conscripts were sent to the front line of the Soviet front with inadequate equipment and protection. Under these circumstances, the death rate among them was very high.

Labour servicemen from Szatmárnémeti in Ukraine, 1942/1943 (Source: szatmar.us)

In March 1944, German troops invaded Hungary. The overwhelming majority of Transylvanian Jews were aware of a sense of danger, yet they did not think of fleeing, trusting in the protection of the Hungarian state until the last moment. The few who realistically assessed the political situation resorted to illegal border crossings (towards Romania) or went into hiding.

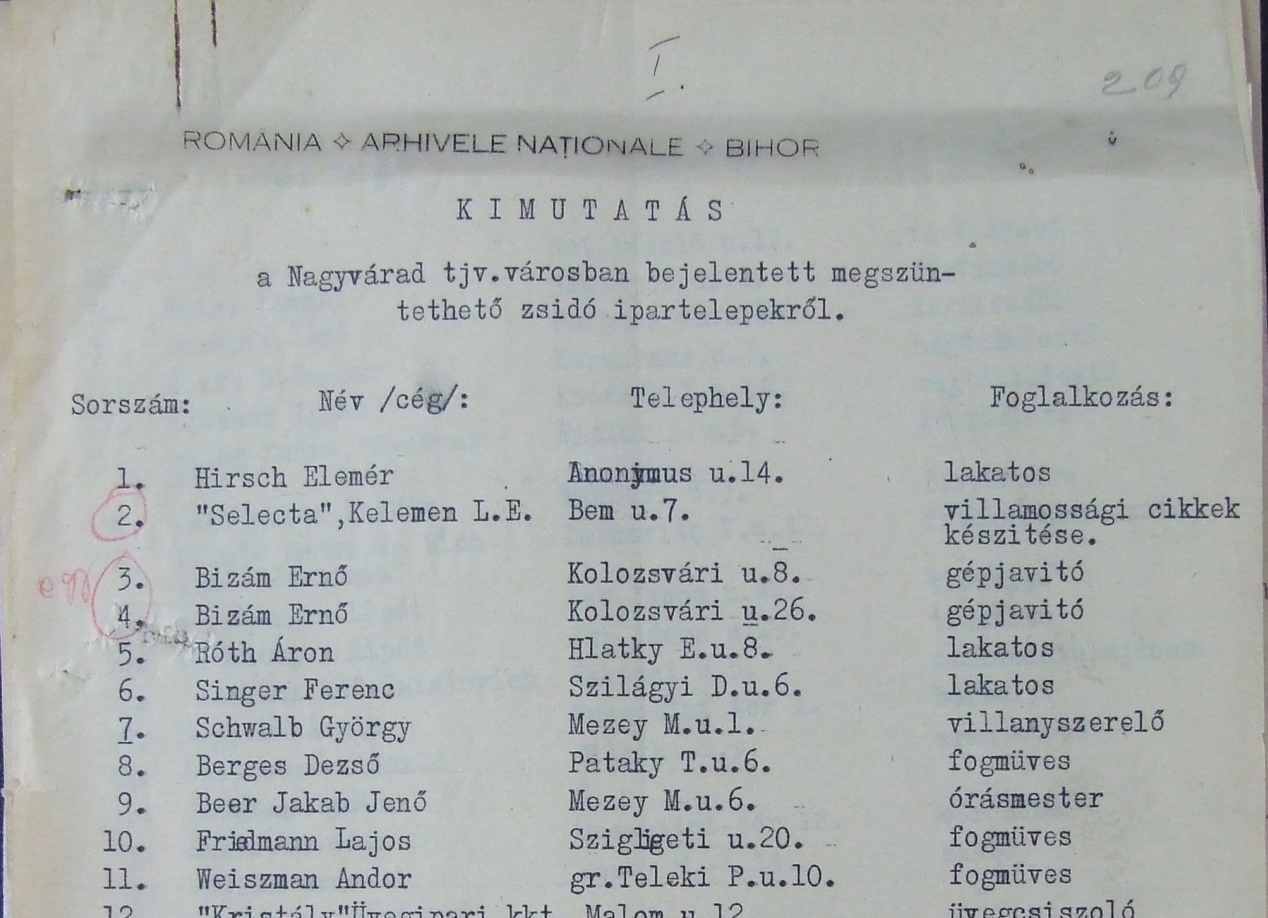

Jewish businesses closed down, Nagyvárad, 1944 (Source: Romanian National Archives, Bihor County Branch)

From 3 May 1944, the Jewish population of Northern Transylvania was rounded up in the ghettos set up in the territory of gendarmerie districts IX and X, which belonged to ghettoisation zone II. Between May and June 1944, the Hungarian authorities dispatched 45 train trains from northern Transylvania to Auschwitz. The majority of the Christian population was indifferent or hostile to the suffering and deportation of the Jews who were awaiting their fate in the terrible conditions of the ghettos. Among the few who helped, common historical memory counts Áron Márton, Catholic Bishop of Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia), who spoke out against the persecution of the Jews in the Church of St. Michael in Kolozsvár (Cluj) on 18 May 1944.

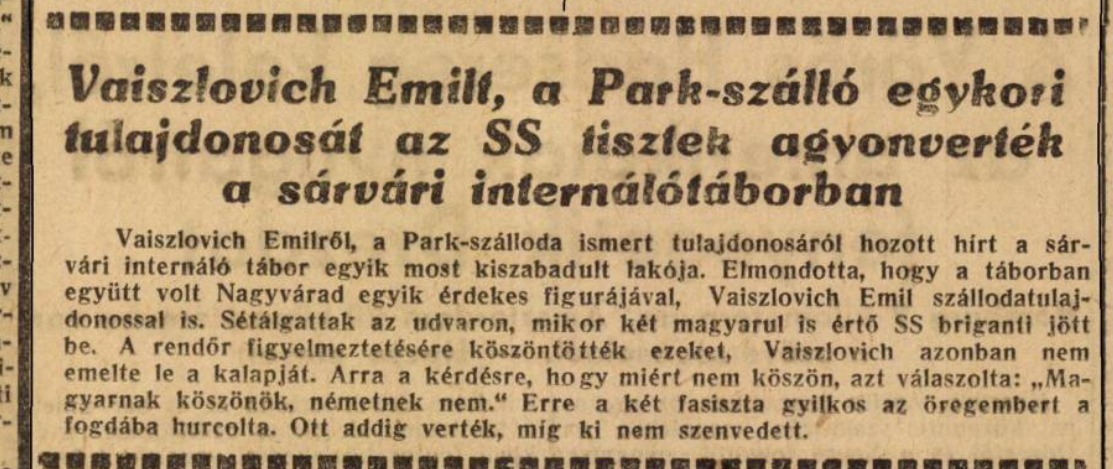

Új Élet (Nagyvárad), 22 April 1945.

Of the 164,000 Jews in Northern Transylvania, only 35-40,000 survived the Holocaust. Of these, about 20,000 returned home from the Nazi camps and we know them by name. 8000 to 10,000 liberated deportees did not return home but went straight to the West. The other survivors returned from labour service. Southern Transylvania, which remained under Romanian rule, lost nearly 41,000 Jews – lot less than the northern region, occupied by Hungary.

Therefore, after the war there were about 75,000 to 80,000 Jews in North and South Transylvania. However, due to internal migration in Romania, by 1947, their number grew, and there were approximately 90,000 Jews living in the region.

The disillusionment with the new communist world order and the establishment of the Jewish state (Israel) in 1948 led the majority of Romanian Jews to leave the country: between 1948 and 1995, some 272,000 Romanian Jews emigrated to Israel. Half of the post-Holocaust Jewish population of Transylvania emigrated until 1952. A significant number of the Transylvanian Jews who settled in Israel retained their Hungarian language and cultural ties.

According to the 2011 census, 3271 people in Romania declared themselves as Jews, of whom 1103 lived in Transylvania.