"I thought I would kill someone in a rage" - The Road of Labour Servicemen from Pestszentlőrinc to Gunskirchen

During World War II, Hungarian Jews were forced to perform unarmed labour service under military supervision. Before the March 1944 German occupation of the country, this was a dreaded institution. The Jews were initially employed in the hinterland: building bridges and roads, digging trenches under heavy military guard. They were mocked, insulted and humiliated, and were often physically abused, slapped and tied up by their captors. From 1941 they were directed to the Eastern Front in the ranks of the Hungarian army which joined Nazi Germany’s war against the Soviet Union. They built bunkers, dug defensive lines and swept mines. They worked under artillery fire, at the mercy of the harsh Russian winter and the increasingly brutal behaviour of their guards. It is no wonder that in less than three years, some 25,000 Jewish labourers died or disappeared.

But with the Nazi invasion of 1944, there was a sharp change: suddenly, labour service became an alternative to deportation, Auschwitz and the gas chambers. Those who were called up were supposed to be released even from the ghettos. (Although in practice the German police and Hungarian authorities who carried out the deportations prevented this wherever possible.) As the front moved further and further west, so they moved closer and closer to death. Their route led from the Budapest area to the labour camps set up in Western Hungary and the Austrian-Hungarian border region, and from there to the German concentration camps. This was the trajectory of Jewish labour servicemen as well as female forced labourers at Pestszentlőrinc near Budapest. Their recollections allow us to reconstruct the main stages of the process.

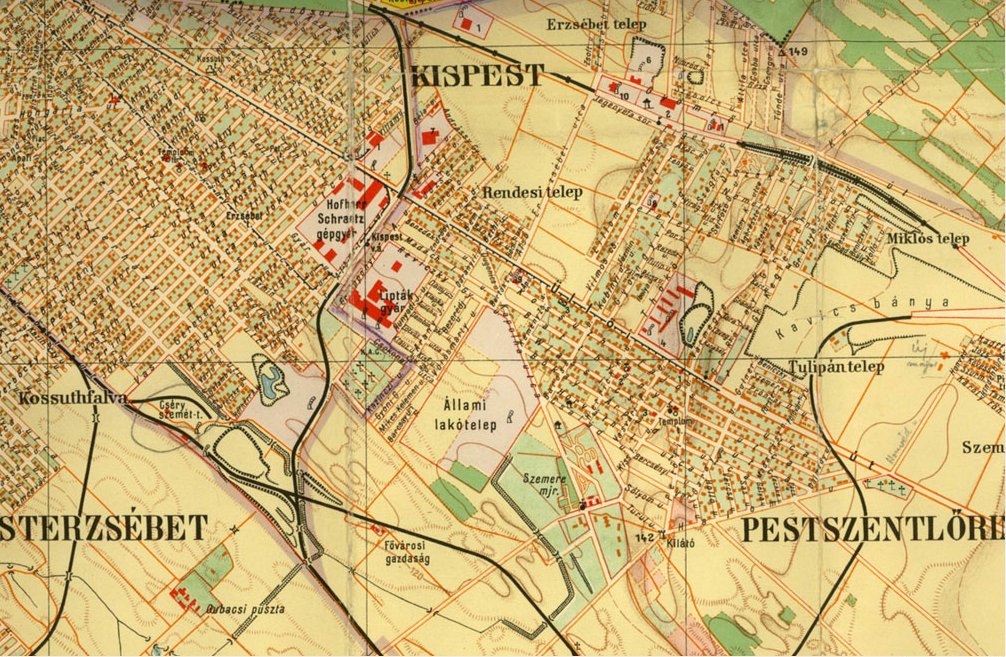

Pestszentlőrinc before the Second World War

Jewish labour servicemen were already employed in Pestszentlőrinc on several occasions between 1942 and 1944. At the beginning of the Second World War, about 60,000 people lived in the then-independent town, which was later annexed to Budapest (District XVIII) in 1950. The military authorities had already been sending labour servicemen here since the autumn of 1942. For a while they had to shovel snow, then in early 1943 they were sent to the Eastern Front. There they worked for months for the Germans in a peat mine. Later, they were sent back to the army: they performed timber work and delivered supplies, while they kept on marching back towards the Hungarian border. After two years of labour service, in February 1945, the military authorities in Sopron handed them over to the Germans again to work on fortifications.

In the autumn of 1942, another labour unit built a road in Pestszentlőrinc. The members of the unit toiled under the command of a captain named Lajos Sz. Nagy. "The treatment was bad," recalled a 40-year-old Budapest survivor, Sándor Bruder, who had previously worked as a tailor in Budapest. The antisemitic commander "harmed us wherever he could". In the spring and summer of 1943, several groups of new Jewish labour servicemen were sent to Pestszentlőrinc. Some were brought here from Ukraine, others from around the capital. Most of the members of the company were tailors who were soon transferred to the National Clothing Institute in Budapest. They belonged to at least two companies (No 101/65 and 101/36) and sewed uniforms (jackets and shirts) for the army at the factory. The treatment was poor, and many of the leaders of the guard staff were antisemitic. "War sergeant Dezső Tóth Horgosi ... did not even deny that he hated the Jews on principle, he thought they should all have been exterminated," Bruder recalled after liberation. Only those could get leave who bribed the company commander Rezső Nagy or another superior with clothes or money. Others received jewellery from the labour servicemen telling them they would deliver the valuables to their families. Instead, everything was stolen and no complaints could be made. Meanwhile, another labour unit (company 101/65) was being terrorised by Lieutenant Márton Pellényi.

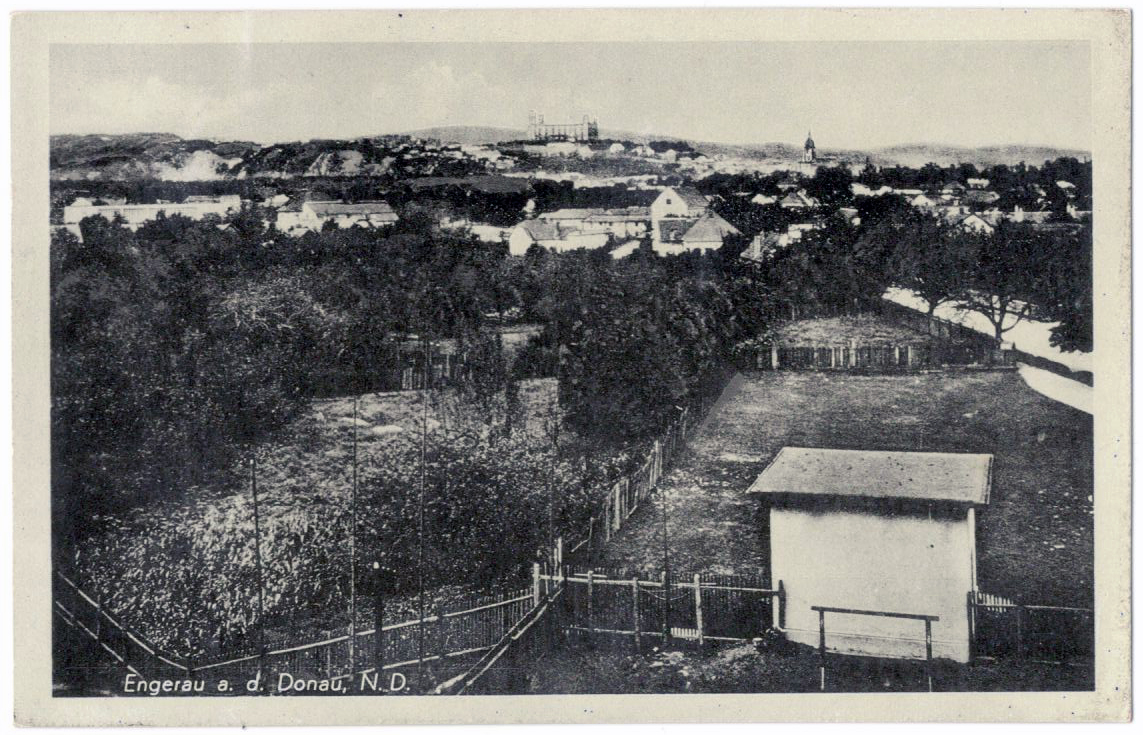

After the pro-Nazi Arrow Cross took power in October 1944, the treatment became even more brutal. Company commander Dr Nagy, in addition to the usual Jew-bashing, beat them with a stick. He accused two of the labour servicemen of escaping and shot them himself. On November 28, 1944, the 250-300-strong unit was taken to a Budapest train station and herded into cattle cars. They travelled for four days without water, bread and toilet buckets. On 2 December, they arrived at the western border in Engerau (Petržalka, Pozsonyligetfalu in Hungarian, now a district of Bratislava), which had been annexed to Germany.

View of Engerau

In and around the village, the Nazis set up a number of small work camps. In these, between 1,700 and 2,000 Jewish labour servicemen were employed in the construction of a fortification line that was supposed to protect Germany from the approaching Soviet troops. The guard staff consisted of Austrian SA men and Nazi Party militia. The men who once served in Pestszentlőrinc dug anti-tank ditches. The conditions were terrible everywhere: they lived in barns and stables, slept on rotting straw, worked in pouring rain and snow. Many died of typhus or starvation. German guards shot people dead for "the slightest irregularity. One after another, the few friends we had grown close to died... in the evenings we listened together, shivering and happy, to the distant thunder of Russian guns, hoping that by the time they got here we would still be here," recalled one survivor. It also happened that the Nazis "simply came in for lunch, and whomever they didn't like, they shot dead", Sándor Hirschorn, a tailor deported from Budapest later recalled. After liberation, the bodies of 560 Hungarian Jews in the area were exhumed.

After the Arrow Cross takeover, more forced labourers were driven to Pestszentlőrinc. From the end of October, they worked in the vicinity of the Budapest airport. They dug trenches and built fortifications. Dr. András Somogyi, a 34-year-old doctor from Budapest, escaped from his unit before the Arrow Cross coup, but was soon arrested again. His company of 250 men was first employed in a number of villages around Budapest. Initially they were guarded by regular Hungarian soldiers, who treated them well, and for the most part the food was acceptable. Soon, however, Arrow Cross militiamen arrived and took them to Kispest (another town neighbouring the capital) to dig trenches. There the Jews had to work from 6 a.m. until 9 p.m. According to the unit doctor: 'We could not even meet the most elementary requirements of hygiene, we lived in a completely animalistic existence, we had no medicines or bandages". Afterwards they were sent to Pestszentlőrinc for a few days, from where about half of the labour servicemen successfully escaped. When the Red Army was drawing nearer, the Arrow Cross took the rest of the Jews to the brickworks in Óbuda at the end of November and then marched them westward. Some were taken to Komárom, but most were marched to the present-day Austrian (then German) border. They were sent to labour camps in and around Kőszeg and built the so-called Südostwall defence line.

Another evacuation followed in March 1945. For the second time in half a year, the Nazis took the labour servicemen westwards so the Soviet army would not liberate them. Whether they were working in Kőszeg, around Sopron or in Engerau, all groups were sent to the dreaded concentration camp of Mauthausen near Linz.

The gate of the Mauthausen concentration camp today

There was a female slave labourer (Frida Lax), formerly also incarcerated in Pestszentlőrinc, who was forced by the Nazis to march around with her companions in the Austrian mountains for 17 days. (She was not deported as part of the labour service system, but was taken from Budapest as a civilian with tens of thousands of others by the Arrow Cross in November 1944.) They received almost no food or water, and the ones who were left behind were shot dead by the German guards. The march of the survivors from Engerau started on 29 March 1945. The 102 sick prisoners who remained behind in the hospital were shot dead by the Nazis. The others were taken to Altenburg, where they had to board barges. During the six-day journey they were not fed, but drank the water of the Danube. The dead were thrown into the river. They finally arrived on 6 April, but on disembarkation the guards shot those who were sick. Only 52 survivors from a unit of 154 reached Mauthausen.

At the beginning of 1945, the evacuation of the concentration camps flooded Mauthausen with an unprecedented mass of prisoners. The administration collapsed and the incoming transports could neither be fed nor housed. The mortality rate rose to 44 percent, with 53,000 prisoners dying in four months. "There were so many of us in one barrack that it was barely possible to sit. We were full of lice and starving," recalled György Glasser, a 29-year-old tailor from Budapest who had also worked in Pestszentlőrinc. Others had no barracks to be lodged in, they were crammed into tents, but before that the SS shot those prisoners who were sick. "Hunger, dirt, sickness, different kinds of typhus, typhoid fever and typhus of the stomach. There was a terrible sergeant in the camp who constantly made our lives miserable. He used to walk with a huge stick, beating the hell out of anyone he caught," the Budapest doctor Dr András Somogyi later reported. When the overcrowding became unbearable, the SS camp commander ordered a partial evacuation.

Mauthausen: moments of liberation in spring 1945 (National WWII Museum)

Most of the Hungarian prisoners were driven to the unfinished camp near Gunskirchen in mid-April. They covered the sixty-kilometre distance on foot in three to four days. Along the way, the guards executed hundreds more. Those who could not keep up and sat down were shot. With no food distributed, the prisoners, mad with hunger, ate grass and snails in their agony. Anyone caught by the guards was shot. In Gunskirchen the survivors were placed in half-finished barracks in the middle of the forest. They did not have to work. For breakfast they were given three decilitres of “coffee”, for lunch less than half a litre of turnip soup, and for dinner a small piece of bread with two decagrams of margarine. There was no water. "There was no washing at all, and so thousands of lice swarmed over everyone in a very short time. No wonder then that a strong epidemic of typhus began, which killed a great many people. We did not dare to report those who became sick because we found that they were shot immediately" recalled the aforementioned Sándor Hirschorn (Company no 101/65).

Food distribution also stopped in the last days of April. Dr Somogyi described the conditions as follows: “200 deaths a day. Constant beatings. The atmosphere was terrible, until the news of the Americans' approach began. When we first heard the news, we were quite shocked and almost beat the messenger to death. We found it outrageous and distasteful that in this terrible misery another comrade should try to mock the others by such an impossible statement." By this time so many had died of starvation that they could not even bury them. Most of the SS guards left on 3 May. Two days later, the American troops finally arrived. Dead bodies were lying all over the camp and in the woods. "They were lying out in the yard, in the barracks, at the latrine, spreading the diseases. The many naked corpses, dried to bare bones and skin, gave off a terrible smell and were a horrible sight," recalled the Sándor Hirschorn. According to another labour servicemen, only 32 of their 180-man company survived the ordeal.

Gunskirchen: what the liberators found (Holocaust Encyclopedia)

The 40-year-old tailor, Sándor Bruder, who had also previously served in Pestszentlőrinc, left for Budapest on foot as soon as the liberators arrived. He did not get far, collapsing after a few kilometres. The Americans took him to hospital. He lay unconscious for weeks with typhus. After he recovered and finally made it home safely, he found his wife and two children alive in Budapest. However, their two-room apartment - from which they had to move in 1944 - was occupied by a Christian couple. The new tenants wanted to chase away the Jewish woman and her two children. "They were finally allowed to stay in the kitchen with great difficulty, and they lived in the rooms and used my furniture. When I came home this week and heard that this could be done to a deported family with impunity, I thought I would kill someone in a rage. I made a noise, which scared them and they let me into one of our rooms, where the four of us now live." – said Bruder in his 1945 testimony.