“There were mountains of corpses everywhere” - Hungarians in Wöbbelin (KL Neuengamme)

In autumn 1938, the SS bought a disused brickworks yard in Neuengamme, on the outskirts of Hamburg. The plant was expanded and production restarted with prisoners transferred from other camps. In the spring of 1940, new barracks were built, barbed wire fencing was erected and the Neuengamme concentration camp began its operations.

The Neuengamme complex

The Nazis initially had the prisoners build a railway and canal in the area. Their numbers were generally around 4,500 in 1941-1942, reaching 10,000 in 1943 and 54,000 by 1945. Increasing British air raids generated more and more orders for the brickworks. Up to a tenth of the prisoners were German. In 1942 most of the camp population were Polish deportees and then Russian slave labourers as well as ca. 30,000 Western European political prisoners (in order of numbers: French, Dutch, Belgian, Danish, Norwegian). As the prisoner population grew, the Nazis established a network of subcamps around the main camp at Neuengamme. These included incarceration sites of all sizes from lodging of 10-man work teams to several thousand-strong camps.

In the early years, the number of Jews was negligible. In 1944, however, the Nazis deported 12,000 people in a short time. Most of them, more than 7,200 (via Auschwitz-Birkenau), came from Hungary. Four-fifths were women, the rest men. The Hungarian Jews were scattered in several subcamps performing forced labour: slaving away on construction sites and in ammunition factories, cleaning up rubble. From March 1945, as the Allied troops approached, the SS evacuated the subcamps one by one. The prisoners were sent to various destinations. Thousands were transferred to Bergen-Belsen and other camps, but the prisoners from the subcamps of Braunschweig, Fallersleben, Salzgitter and Porta were taken to a new assembly camp set up on the spot: Wöbbelin.

Wöbbelin

The SS opened the Wöbbelin subcamp near the town of Ludwigslust in Mecklenburg. Originally it was intended for US prisoners of war, but then the concept changed. The first 700 prisoners arrived on 12 February 1945. They built the new camp: several stone barracks, including bunkhouses, a kitchen and a bathroom.

The main gate of the Wöbbelin camp (US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

In April 1945, the evacuation of the Neuengamme complex led to an influx of transports to Wöbbelin. Even a transport from Auschwitz arrived via Ravensbrück. Most of the deportees were French, Dutch and Polish. The prison population rose to 5,000. But the half-finished camp was nowhere near able to accommodate such a crowd.

The floors of the barracks were swarming with insects and worms. Roofs lacked insulation, windows lacked glass, doors were not there at all. A few prisoners had improvised bed frames from sticks and logs, but most were forced to lie on the floor.

Bunk beds made by prisoners in a barrack in Wöbbelin (US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

The water was contaminated and anyone who drank from it became ill. In the absence of any other solution, the bodies were piled up in the barracks, which had originally been used as a bath, making washing impossible. Food rations shrank because the original rationing was planned for a lower number of prisoners. So great was the hunger that cannibalism appeared in the camp: some of the starving prisoners ate from the corpses.

With the arrival of the transports, work stopped and constructions were halted. Only the corpse-carrying units, to which most of the prisoners had volunteered because of the double rations, worked regularly. The bodies were dumped in open mass graves, but these too soon filled up. The SS originally intended Wöbbelin to be a reception camp (Auffanglager). But now it became a real death camp (Sterbelager), where the sickest, weakest, dying prisoners of the Neuengamme complex were gathered.

Paul W. Hoppe, later SS commander of the Stutthof concentration camp and later Wöbbelin (Jewish Virtual Library)

The commander was SS-Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant-Colonel) Paul Werner Hoppe, the former head of KL Stutthof on the Baltic coast in Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland). As Stutthof was evacuated due to the approaching Soviet troops, he had been left without a commission. The new Kommandant brought with him his brutal regulars (Hauptsturmführer Meyer and Obersturmführer von Bonin) and part of the guard staff. He did not particularly care for the infernal conditions in Wöbbelin. Even if he sometimes appeared in the camp, his main focus was on the construction of the command building and the SS headquarters.

The camp fence (US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

János Fejes and Péter Schlesinger were deported by the Hungarian authorities from Budapest in December 1944. They were first sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp and then to the Neubrandenburg subcamp. Then, although they were men, they were transferred to the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp. The main area of the camp was “full of corpses, a sight that was terrible to behold”. Many of their comrades died because their bodies could not cope with the fatty food found in the Red Cross parcels distributed. Five days later they were taken to Wöbbelin. “Hundreds of people died every day because of typhus and terminal weakness. The dead and dying lay among us, with no one to care for us. Besides, we were all completely weakened, because there was absolutely no care for our food."

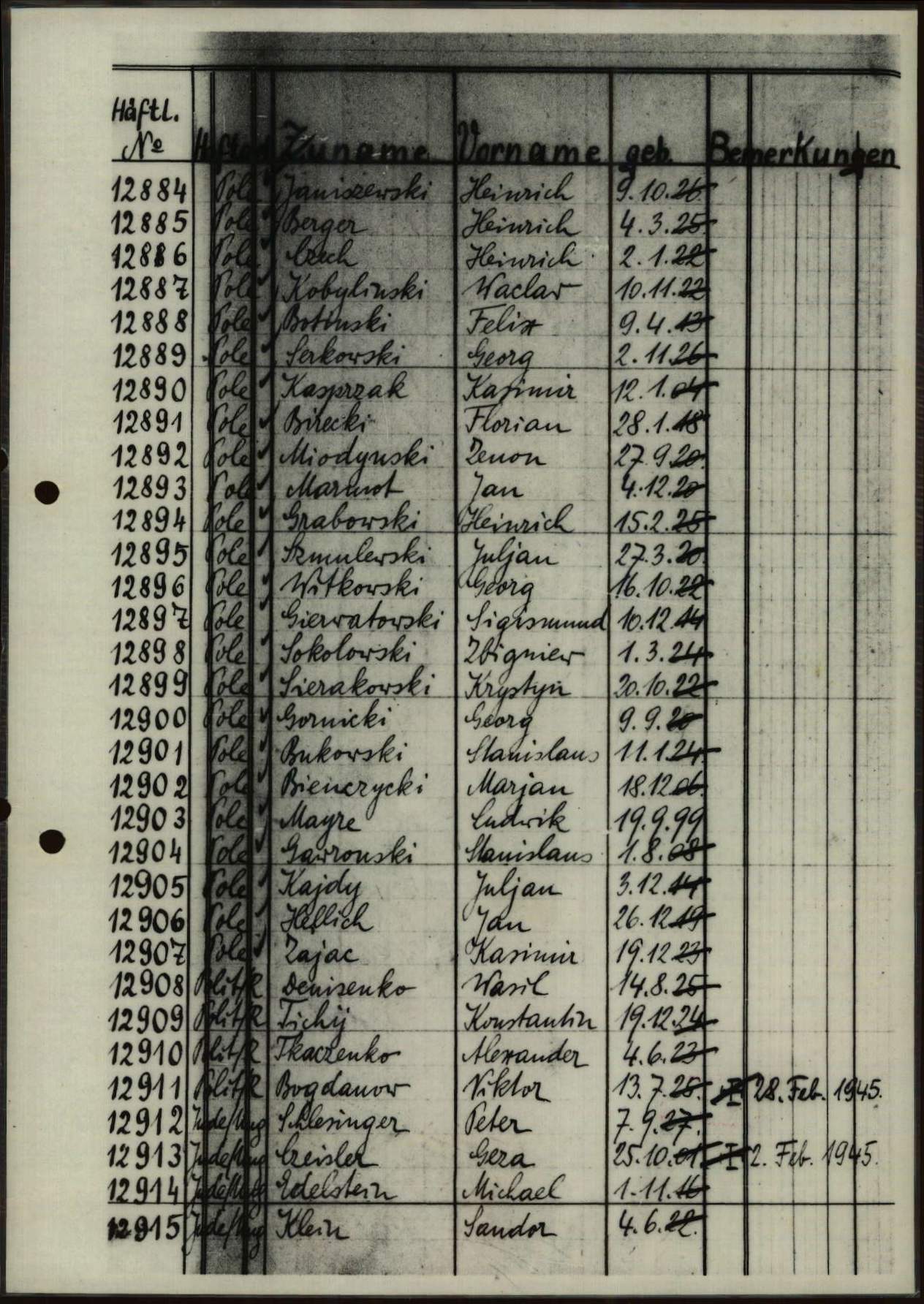

The name of Peter Schlesinger, number 12912, on the list of names from the Ravensbrück concentration camp (Arolsen Archives, ITS)

Another labour serviceman, 17-year-old János Erdős, arrived on the same transport from Ravensbrück on 26 April. "We were taken to a half-finished camp, we lived in stone barracks, without doors, windows, beds, 1000 of us in a block, we received 3/4 litre of soup and 1/8th of bread ......4 and out of 5000 people, at least 50-60 people died every day, most of them from diarrhea, there was no medicine, so the sick died without any medical help. The German Kapos beat people with sticks and rods. In the barracks we didn't even have enough room to stretch our legs, of course at night there was always loud wailing and shouting, and then the Kapos came in and beat people to death. It was the same with food distribution, if we didn't stand straight enough or in line for food, so very often we would forgo lunch instead."

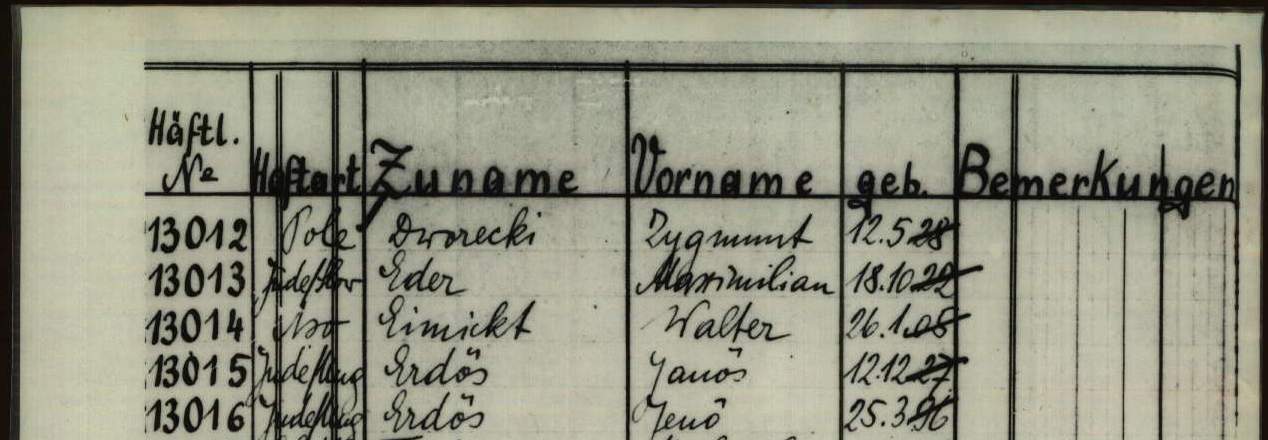

Same list of names from Ravensbrück, with prisoner number 13015 János Erdős (Arolsen Archives. ITS)

Pál Smilovits was also a labour serviceman. A 40-year-old Budapest merchant, he was taken by the Hungarian military in a forced march from the mines of Bor in Serbia to the Austrian-Hungarian border. There the SS put the survivors on a train. They were taken to Ravensbrück, then the Barth concentration camp and eventually they arrived at Ravensbrück. By then only 27 of them were alive. Then came Wöbbelin: “We had an average of 100 dead every day dying from exhaustion”, he later recalled.

At the end of April 1945, due to the approach of the Americans, Commander Hoppe started the evacuation. During a roll call, the SS separated the prisoners unfit for transport from those who could travel. The first group had to stay in the camp. The rest were crammed into railway cars. However, the train never left. “We were lined up and put on the train on 1 May. We spent 24 hours in the tightly closed train cars where we could hardly stand on one foot. In the morning they let us out of the car and chased us back to the camp with big dogs. During the chase, a lot of our comrades were shot dead. That night, there were at least 6-8 dead bodies in each car, which were thrown out on the road” - Erdős reported after the war. In the camp, the bodies of those who had tried to hide from the transport the day before were scattered. They had been shot, but the sick were spared this time for unknown reasons.

The next day, Hoppe's men again rounded up a few hundred prisoners, and marched them on foot towards Schwerin. However, the column soon ran into the US tropps and the SS guards fled. Two American medics were the first to enter the camp on 2 May. James M. Gavin, commander of the liberating 82nd Airborne Division wrote in his memoirs that the troops could smell the stench of Wöbbelin before they even saw the camp. The Americans found 3,500 prisoners and something they had never imagined before. “The Americans were horrified to see the terrible sight: heaps of corpses everywhere. In the revir [infirmary], hundreds of dead bodies lay among the sick " - said Erdős in his post-war testimony.

Wöbbelin Survivors (US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

The aforementioned Pál Smilovits described the first days of freedom as follows: “The Americans treated us in such a way that we would never have such a good time in our lives again. They gave us an unbelievable treatment. It is impossible to describe how self-sacrificing they were. We can never repay them for all their kindness. Sadly, even after liberation, many more [prisoners] perished. The Americans fought a lion's fight for the lives of every single prisoner. They spared us nothing in the world. For example, they had a blood transfusion machine, it cost 100 dollars for a transfusion, and there were patients who received ten. They did everything for us."

Despite these efforts, more than 200 starving, sick deportees died after liberation. Among them was 65-year-old Dr. Dezső Kornhauser (Kornhausen Desiter), who died on 4 June 1945. Angry Americans drove the surrounding German population into the camp to see the bodies and had them bury the victims. In just ten weeks of its existence, more than 1,000 prisoners died at Wöbbelin. The number of Hungarian victims is unknown. It seems that the earliest of them to die was Gusztáv Kovács (prisoner number 75070), aged 30, on 21 March 1945. The other Hungarian Jews died in late April, in the days immediately before liberation. On 25 April, Artúr Friedenthal (born 1903), on 28 April, Ferenc Polgár, on 29 April, Béla Goldberger (born 1909) and 18-year-old János Fried (born 1926), and the next day, Artúr Fried (born 1907).

German civilians were ordered by the Americans to visit the Wöbbelin camp (US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

After the war, the fugitive camp commander, Hoppe, was arrested by the British. But not for what he had done at Wöbbelin, but for his role as a Stutthof commander. Hoppe later fled to Switzerland to escape conviction and then returned to his home country, where he was again detained. Sentenced to nine years, he was released in the late 1960s. Although the West German judicial authorities opened an investigation into the crimes committed in Wöbbelin after a delay of 20 years, the case was eventually dropped for “lack of evidence”.