"She had a rubber baton with iron pins on the end" - Hungarian Slave Labourers in Unterlüß (KL Bergen-Belsen)

The Nazis set up a subcamp in Unterlüß by the name “Lager Tannenberg” about 35 kilometers from the notorious Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. The first prisoners (ca. 800 to 1000 people) arrived from Auschwitz-Birkenau in August 1944. All were Jewish women: some were Polish, some were Yugoslav, but the vast majority were deported from Hungary. Before departure, they were selected by the dreaded SS doctor, Dr. Josef Mengele, so, as one survivor later said, they feared “we were going to the crematorium”. But when they boarded the 50-person train cars, they were met by elderly German soldiers instead of SS men. They were given supplies for the journey and three days later arrived at the Rheinmetall-Borsig AG munitions factory in Unterlüß.

Birkenau vs Unterlüß: accommodation and hygiene

Their first impressions were favorable - at least compared to Birkenau: “On arrival we were given a fine soup, everyone had their own spoon, plate and cup. Here we had 2 blankets per person, and everyone had a separate bed. Now we were very happy to sleep in separate beds and not have 14 of us eating from the same pot without a spoon”, recalled six women deported from Huszt after the war.

Remains of a barrack of the Unterlüß subcamp (Wikipedia/Hajotthu)

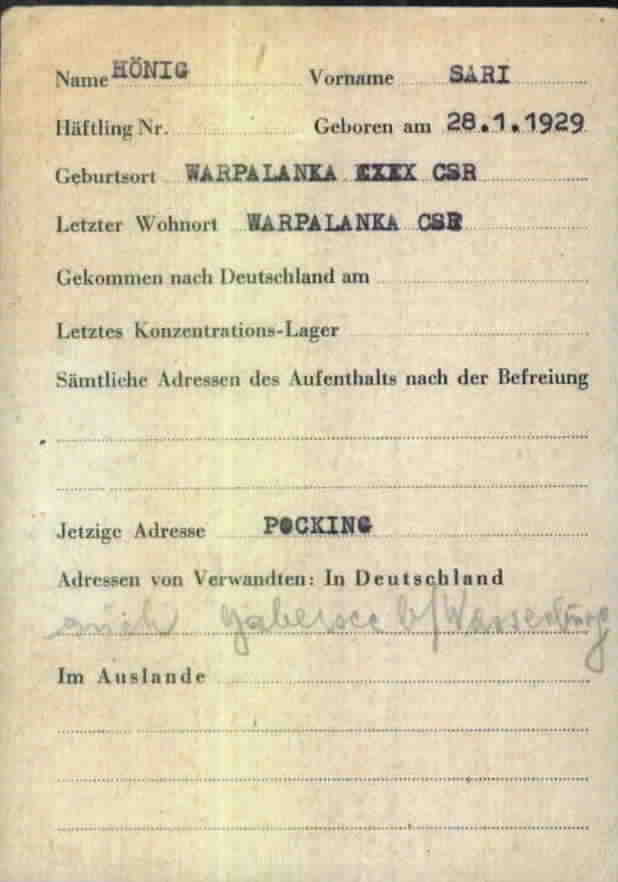

According to the Hermann girls from Munkács: “Our accommodation was quite good. We stayed in barracks, each with our own bed and two blankets. Everyone had their own plate and cutlery. We could wash ourselves and we were clean, only later the transport from Bergen-Belsen brought lice among us, so we also had an outbreak of typhus.” Another two prisoners from Munkács emphasized that everyone could sleep in separate beds and that they were given two blankets each: “The accommodation was not so bad, because in winter we could heat the room, and there was a washroom, so we had the possibility to clean ourselves.” Sári Hőnig, 16, from Várpalánka, liked the fact that “we had a way to keep it clean...(and) the camp was in a nice place in the middle of the forest.”

Forced labour in the Nazi war industry

Those who were comparatively fortunate were assigned to the Rheinmetall munitions factory, where they had shelter, initially received adequate rations, and were not subjected to extreme mistreatment. However, the labor was physically demanding and hazardous to health. Over time, food supplies diminished, while instances of violence and brutality increased.

The Spiegel girls from Munkács (Irén, Hajnal and Frida), aged 14-22, were given 40 grams of bread and carrot soup a day, and they were not harmed in the factory, not even by the SS. Two other Hungarian survivors mentioned shrinking rations: “The work was quite hard. We got up at 4 in the morning and were ready at about 5.30 a.m. when we went to work, and we worked until 7 p.m. in the summer and 4 or 5 p.m. in the winter. The provisions here were no better than in Auschwitz. In the morning, we got a little soup, in the evening also soup, about 20-25 grams of bread and a little Zulage (extra ration).”

The identity card of Sári Hönig, born in Várpalánka, issued in the Pocking camp after liberation (Arolsen Archives ITS)

The aforementioned Sari Hönig was also sent to the ammunition factory: “I was taken to work by train. The work was hard, we worked on rusty machines. We cleaned bombs and filled them with yellow sulphur powder. It turned our hands and hair quite yellow, and you can still see the traces of it... We certainly went hungry a lot. In the factory they gave us a quart of milk at noon, otherwise we couldn't have done the hard work in the factory. We were treated well at the workplace."

As a foreman, 18-year-old Mária Simkovics closely observed the production process: “We were making 14-kilogram bombs, and I was injured once, because of a machine malfunction, there was a gas leak, and almost everyone got sick. The work was supervised by SS men and Aufseherins (female overseers), with very strict treatment, we were not allowed to talk to each other. If the required work was not done on time, we were beaten, and this was a daily occurrence because my fellow prisoners' health had deteriorated to the point where they were no longer able to work. The daily rations consisted of 25 grams of bread and empty soup."

Hunger, cold and beatings: working outdoors

Many Hungarian deportees suffered even worse. They were forced to work outdoors in various work teams despite the cold. They were made to do all kinds of work. Sarolta Lőwy, 20, was sent to work in forest logging. They woke up at dawn to the sound of a whistle, “just hearing it was sickening”. The prisoners went to work in the dark: “It wouldn't have been very difficult if we hadn't had to work in winter in nothing but our plain clothes, our shoes always stuck in the snow.”

Remains of the Unterlüß subcamp. Hungarian Jewish women did logging work in this forest (Wikipedia/Hajotthu)

Others complained about the cold and inadequate clothing. In many barracks there was no heating, and many prisoners walked barefoot in the snow without shoes, wearing summer clothes. Rózsi Moskovits, 21, from Iza, and her companions carried stones “We dug a big pool, it was terribly hard work. We also had to cut wood for the work, later we had to build a road. We were constantly starving. We were given 1/6 loaf of bread a day, we couldn't drink water all day, we didn't eat anything for breakfast. We had to wake up at 2 o'clock in the morning. We worked until 10 o'clock at night. Sometimes we had to carry rails and lay them down, it was terribly hard, but if we didn't work enough, we were punished...”

Many survivors highlighted the brutality of the SS guards. Edit Lichtenstein, for example, was assigned to clear debris and then build a road. She was given a liter and a half of soup and 200 grams of bread a day. Mrs. Gyula Braun confirmed this. She arrived in February 1945 via Gross-Rosen and Mauthausen. They were on the road for eleven days and then worked in Unterlüß, where they worked in the forest, doing logging. “We worked 12 hours a day, under the strict supervision of the SS, who constantly kicked us.”

“When we went out in the morning, we were freezing in the winter, we didn't have a coat until Christmas, so we arrived at work every day in a terrible state. We used to put cement bags on ourselves, but if they noticed it while beating us, the person was tortured to death,” said another woman later. Others complained about the brutality of the Polish kapos (prisoner functionaries).

Based on survivors' recollections, it seems that the commander of the subcamp, SS-Commander Friedrich Diercks, was relatively unseen. The guard consisted of 18 SS guards and 3 female overseers. The lives of the prisoners were mainly determined by Captain Rudolf Wandt and, in his absence, by SS Sergeant Stecker (elsewhere: Stocker). The monster of the camp, however, was clearly a young female SS overseer, Susanne Hille.

Irma Grese and SS commander Josef Kramer of Bergen-Belsen, in British custody. Both were executed (Imperial War Museum)

A sadistic overseer: Susanne Hille

Most of the notorious female overseers in the SS camp universe were undereducated young girls from poor families. For them, this job meant higher pay and a more predictable livelihood than before, the uniform meant higher social prestige, and the boots, gun and lash meant power. Irma Grese, who was convicted and hanged at the Belsen trial, was known as the “hyena of Auschwitz”, used to work in the fields, and used to have jobs as shop assistant and hospital nurse. At the age of 19, she became an overseer, and by the age of 20, 18,000 women (mostly Hungarian Jews) were subjected to her orders in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Hermine Braunsteiner, known as "mare" (Kobyla) to the inmates of the Majdanek camp, who trampled women to death and dragged children by their hair to the gas chambers, originally wanted to be a nurse. She worked in an arms factory, then in an aircraft factory, and finally, at the age of 20, she joined the SS as an overseer, earning four times her former salary.

The Unterlüß killer, Susanne Hille, followed a similar path. Born in Altenburg in 1922, she must have been 22-23 years old at the end of the war. Instead of continuing her education, she started working at the age of 15. She worked as a saleswoman, as a laborer and then as a product inspector (Kontrollarbeiterin) in an arms factory. After joining the SS as an overseer, her career took off. From September 1944 she was Kommandoführerin in Unterlüß. Hille played the same role in the collective memory of Unterlüß as Margot Dreschel and Irma Grese did in the history of Auschwitz-Birkenau and Hermine Braunsteiner in that of Majdanek (KL Lublin).

Many Hungarian survivors remembered her by name. Others referred to her as “the brown one”, others as “the black one”. But everyone agreed that Hille was the worst of the SS. She would always unleash her dog on Mrs. Benő Kroó of Munkács and her fellow inmates during work. Hille constantly insulted, abused, made fun of female inmates, and called them animals. She went through the barracks with a whip in her hand and beat the Jewish women indiscriminately. She beat Edit Balázs, for example, as well as Edit’s sister.

Three survivors from Carpatho-Ruthenia recalled: “When we arrived in Unterlüss, things were better here, we had separate beds and blankets. But there was an SS woman called Susanne Hille here, we never saw her without a rubber baton, she beat us for no reason, it was enough just to walk past her. If she gave us something and we thanked her, she told us not to thank her for anything, because if it depended on her, she wouldn't give us anything. All winter long she would hold back supplies, she wouldn't give us any foot-rags, and if we got a piece of cloth, she would whip us 25 times for that alone.”

Mrs. Fuchs, 50, later said that the torture was carried out according to a precise daily choreography: “The treatment was horrible, we had a terrible, nasty Aufseherin. This one started her work in the morning; when we got up for Zahlappel (headcount), she stood next to the Lagerführer and started slapping us on both cheeks. If one did not fall down immediately, she kicked her until the person collapsed in blood.” According to other accounts, Hille stamped on women who fell to the ground.

Sári Hönig also saw Hille killing people: “...in the camp an SS woman beat us terribly. She punished the smallest thing with 25 baton hits. We wore striped clothes and a sweater all winter. There were no coats. We were given warm stockings, but that SS woman stole them. On one occasion, she stripped us naked, and anyone she saw with a little cloth lining in her cap was shot or beaten to death on the spot.” Sarolta Lőwy was also a witness to Hille's murders: “The Aufseherin was very bad to us: she came every day to check whether we had any warm clothes or organized [i.e. stole] food. If she found anything, she could beat the person to death.”

According to two survivors from Munkács, Szerén and Helén Rochlitz, they were also mistreated by other members of the guard staff under Hille's influence: “We had an overseer who made our lives particularly miserable. She had a rubber baton with iron pins on the end and beat us with it for no reason. Our day of rest, Sunday, was a day of hatred for us, when we were in her hands all day long, and she was not afraid to invent the most elaborate tortures. Our Oberscharführer was a good man, but this woman, who was beautiful for all her badness, infatuated him and made him torture us.”

Bergen-Belsen SS overseers in captivity. First from the right, 191 cm tall Hertha Bothe, who was sentenced to 10 years (Wikipedia)

It is clear from these incidents that Hille did not beat the prisoners on the orders of her superiors, but on her own initiative. She was not a norm follower, but a trendsetter. It was precisely because of her behavior that the abuse and killing of Jewish women became an example for the other guards to follow. In fact, paradoxically, Hille's behavior went against orders. At the end of 1944, the SS leadership was no longer concentrating on killing Jews, but on exploiting them in the war industry. The main objective was no longer to win the war against the Jews, but to win the war against the advancing Allies. To do this, strong and healthy workers were needed. By depriving women, who were freezing to death, of warm stockings, beating up those who had their caps on, stripping them naked in the cold and shooting them, Hille was hampering the very efficiency of the already murderous Nazi war production she had been tasked with improving.

Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that prisoners fell ill and became incapacitated en masse. They were transferred in groups every two weeks to the main camp, where many died. The largest group transferred consisted of 350 prisoners. By February 1945, only 517 women remained in Unterlüß. The fate of Suzanne Hille is unknown. What we know for certain is that, unlike her fellow overseers arrested in Bergen-Belsen, she was never brought to trial.

The liberation

On April 13, 1945, British troops appeared in the area. The SS staff simply escaped. After several hours of uncertainty, the kitchen manager told the prisoners that they were free. Soon, however, German gunmen arrived: reports mention police, National Militia (Volkssturm) and Wehrmacht soldiers. Whoever they were, they gave the order to leave. But then several prisoners refused to obey. Two women who tried to escape were shot. The others were escorted to the main camp. 24 sick prisoners were loaded onto a truck. Among them were the three Hermann girls. Only one of them, Ilonka, was sick, but her sisters refused to leave her alone, so they pretended to be sick and were put on the truck. The vehicle drove into a forest and then stopped. The Germans left and never returned.

The prisoners had been freed, but in the middle of the forest, seriously ill and close to the front, their lives were still in danger. “Late in the evening, a Wehrmacht soldier noticed our unfortunate group in striped clothes, came up to us, we told him the situation, he took pity on us, distributed his bread among us. One of the Polish Jewish girls - who also had typhus - searched until she found some face paint, painted herself up, went up to the Wehrmacht soldier, talked to him, made him like her, until he liked her, and saved us for her sake.” The soldier took the women to Häcklingen, a nearby village and “forced one of the farmers to hide us in the straw. He was not very willing, but our Wehrmacht soldier told him that if a single hair of our head was harmed, the British would kill him. He kept us there for 8 days, with plenty of food, so that all suffering from typhus were cured.” Szerén Sinkovits and Paula Klein were among them. According to their post-war testimony, the farmer hid them in the barn among the straw, giving them milk and bread.

Bergen-Belsen: survivors in one of the barracks after liberation (Imperial War Museum)

When the British finally arrived and saw the condition of the prisoners, “they took care of us immediately. They took us to an apartment, fed us, robbed a shop and clothed us from head to toe.” Later, a British army doctor sent all 24 girls to a hospital in Lüneburg, where they recovered for three months. Despite receiving the best of care, three of the deportees died in the hospital.

The victims

We do not know how many people perished in the Unterlüß camp. In any case, survivors report mass mortality. According to the 22-year-old Lebovits twins Malvin and Fáni, there were already many dead in the munitions factory. According to Mária Simkovics, "When we arrived there were 800 of us, 3/4 of us had died, most of them of lung hemorrhages from the hard work. There was Revir (infirmary), but absolutely no medicine, so the patients could not be cured. There were also many victims of starvation, which caused the people to die of exhaustion.” The dead were taken to the main camp at Bergen-Belsen, where they were apparently taken to the crematorium.

According to Mrs. Braun, in August, thousands of people arrived from Auschwitz-Birkenau to Unterlüß, but by the following spring only five hundred returned to the main camp, where another 100 patients died. Others say there were 300 victims.

SS officers and guards lined up in front of one of the mass graves. The British had them bury the 10,000 bodies found at Bergen-Belsen. After liberation, another 13,800 prisoners died, mostly of typhus (US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

According to reports, many Jewish women, mainly Hungarians, were victims of forced labor in Unterlüß. Some of them died in the subcamp, others died of hunger and typhus after being transported to the main camp. Many died after liberation. One of them, Rózsi Bohdner of Csögle, went mad as a complication of the high fever associated with typhus: “She had constant nightmares, she thought the British soldiers were SS in disguise. She shouted, 'can't you see that they are SS' and finally committed suicide,” said one of her fellow inmates in her post-war testimony.