Sátoraljaújhely, Komárom, Dachau and Spaichingen: Hungarian resistance fighters and political prisoners in Nazi camps

The largest armed resistance action in Hungary during the German occupation was the Sátoraljaújhely prison riot. During the war, the Sátoraljaújhely Penitentiary was repurposed as a prison under the jurisdiction of the Court of the General Staff of the Hungarian Army (Magyar Honvéd Vezérkari Főnökség Bírósága). By the autumn of 1943, it held 423 political prisoners, including 52 women. More than a third (37%) of the detainees were partisans, resistance fighters, and political prisoners from the Délvidék (“Southlands”), a region occupied by Hungary from Yugoslavia in 1941. The majority were Serbs, along with some Hungarians from the Southlands, as well as a smaller number of Croats and Slovenes. In addition to Hungarian antifascists—including communists, social democrats, trade union leaders, and peace activists—a small number of Slovaks, Ukrainians, and Romanians were also imprisoned there.

The treatment of prisoners was generally tolerable, but the food supply and living conditions were poor. Due to the limited number of reserve guards, authorities were unable to prevent detainees from forming clandestine groups within the overcrowded cells. As the Red Army advanced toward the Hungarian border in late 1943 and early 1944, a group of prisoners—led by experienced Yugoslav fighters—began secretly planning an uprising. Their goal was to disarm the guards in the spring and retreat to the surrounding mountains, where they would join the resistance and await the arrival of Soviet forces. Aware that capture by the Germans would mean deportation to a concentration camp, the leaders of the rebellion decided to act swiftly. On 22 March, they launched their attack.

The Sátoraljaújhely prison

The prisoners managed to capture and disarm several guards, but one of them opened fire. The gunshots alerted nearby Hungarian and German troops, who quickly arrived at the prison. A fierce battle ensued, with prisoners resisting using rifles and pistols while machine guns were used against them. Those attempting to escape toward the hills were targeted with mortar fire. The rebellion was brutally suppressed within a short time. Two prison guards, including a sergeant major nicknamed "Bulldog," were killed, along with approximately 20 prisoners—some of whom took their own lives upon realizing the uprising had failed. The Germans attempted to execute the surviving prisoners who had been rounded up in the yard, but the Hungarian prison commander, Lieutenant Lajos Lindberger, intervened. Despite being wounded by the rebels, his persistent protests prevented the executions from being carried out.

Approximately 70 prisoners, including women, managed to escape. In the following days, German forces and Hungarian gendarmes conducted a manhunt in the surrounding villages, capturing and executing most of the fugitives. Forty-five men were put on trial and subjected to brutal interrogations, during which they were beaten with clubs, kicked, trampled on, had their feet pricked with iron, and had hot needles driven under their nails. Ultimately, on 6 April 1944, a court of summary conviction sentenced eleven rebels to death. In total, the uprising resulted in more than 62 victims.

In the Komárom Csillagerőd

In May, some of the surviving prisoners were assigned to labor service in a penal unit, while the majority were transferred to the Csillagerőd (“Star Fortress”) in Komárom in the autumn of 1944. The Hungarian authorities concentrated prisoners from arious facilities, including Vác Prison and the Margit körút Gyűjtőfogház, as well as detainees from internment camps such as Nagykanizsa, which had been evacuated due to the advancing Soviet forces. Following the Arrow Cross takeover on 15 October, prisoners of war, captured Jews, forced laborers, and hundreds of Roma families were also deported to the fortress. Originally constructed in the mid-19th century, the facility soon became severely overcrowded, with 6,000 to 7,000 people confined in unheated cells.

The ’Csillagerőd’ in Komárom

Many prisoners had no shelter and were forced to endure the cold in the open air in the fortress courtyard. Starvation was widespread, sanitary conditions were dire, with insufficient toilets and drinking water, and the lack of bathing facilities led to outbreaks of epidemics, resulting in a growing number of deaths. The small number of guards—only 35 at the outset—was insufficient to maintain control, allowing prisoners, including Yugoslav and Southlands detainees from Sátoraljaújhely, to escape in groups as the army grew increasingly concerned about the possibility of a communist uprising. As the situation became untenable, the Arrow Cross government decided to transfer the prisoners to German authorities for forced labor. The transport was organized by the German Security Police (Sicherheitspolizei – SIPO) in Budapest.

In Dachau

The rebels from Sátoraljaújhely arrived at KL Dachau on 14 November. The “mixed” transport (Sammeltransport) consisted of 1,512 men, including 200 Jews, 175 Roma, and 482 Hungarian political prisoners. The political prisoners transferred from Komárom remained together in Dachau. After being bathed, they were issued striped prison uniforms, marked with the red triangle assigned to left-wing political prisoners.

The prisoners were assigned to the same barracks and immediately convened on a three-story bunk bed. Over the next few days, they learned about the conditions in Dachau from Polish priests, as well as Soviet and French prisoners. Their informants described the camp as a "meat grinder." Most of the new arrivals were skilled metalworkers and suspecting that this skill might be in demand by the Nazis, they decided to volunteer if the SS were seeking such workers. They rationale was that working in a heated factory would offer them a better chance of survival. They elected as their leader Jacob Schaberger, a 29-year-old Transylvanian Saxon (ethnic German) communist (prisoner number 125101), known to all as Jaksi and fluent in Hungarian. Alongside him was 23-year-old Budapest locksmith János Eisner, also known as Kenedi.

A few days later, the Germans began searching for skilled workers for a metal factory. The political prisoners did not hesitate and quickly volunteered. A significant number were soon transferred to various subcamps of KL Natzweiler. The first group of 200 prisoners departed Dachau for the subcamp in Spaichingen on 22 November 1944.

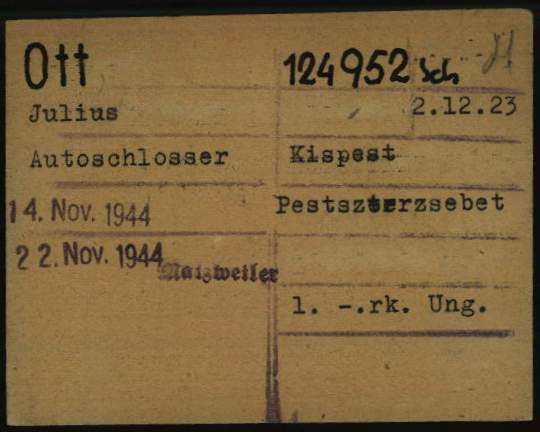

The date of the transfer to Natzweiler was recorded on car-mechanic Gyula Ott's card from Dachau: 22 November 1944 (Arolsen Archives ITS)

More than half of the transferred detainees (on the transport list of 200 prisoners, with serial numbers ranging from 86 to 193) were political prisoners from Sátoraljaújhely. Among them were Hungarian communists and social democrats, Yugoslav (mostly Serb) partisans, as well as some Hungarian Jews and Roma.

KL Natzweiler - Arbeitslager Spaichingen

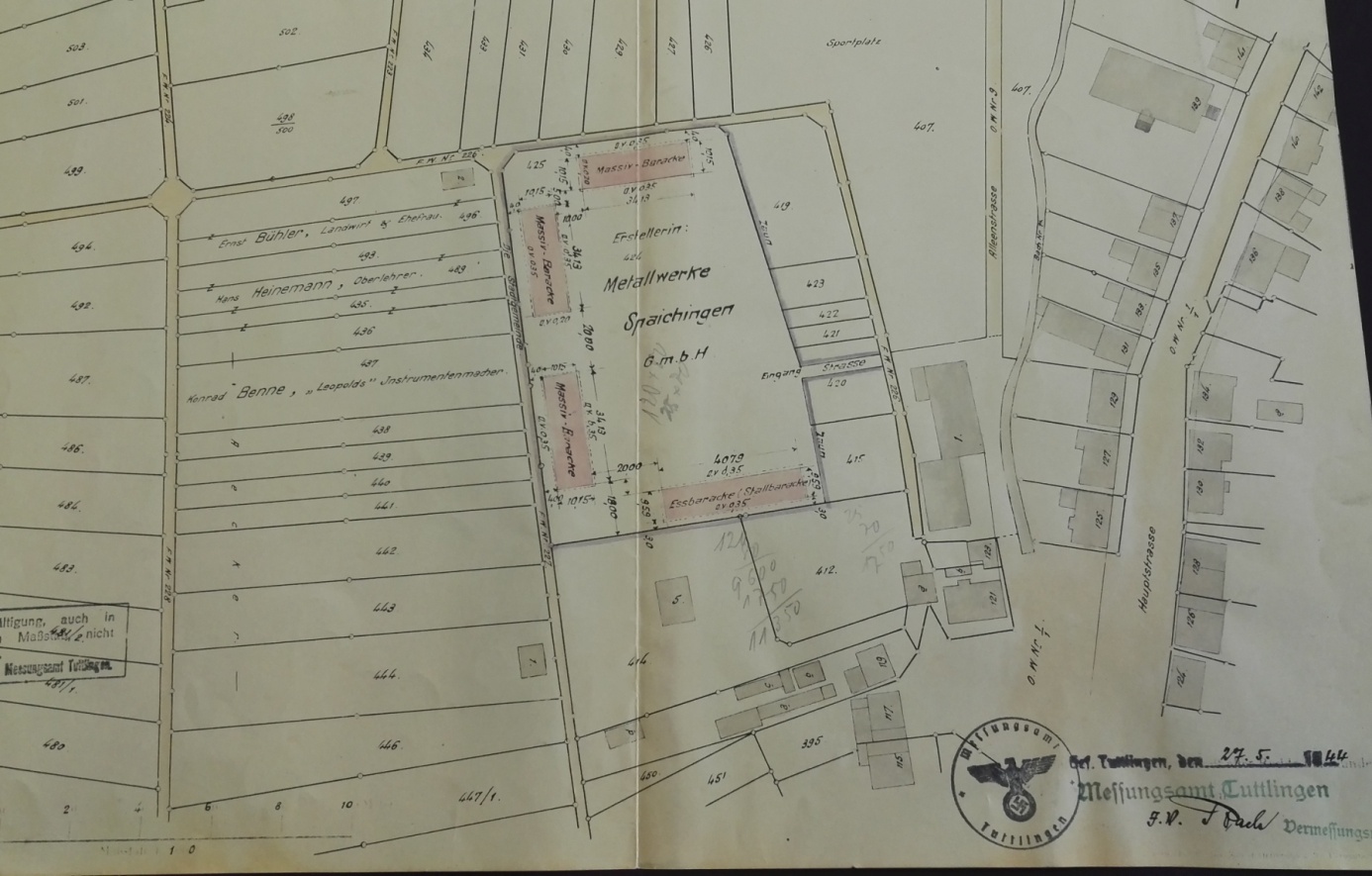

In the autumn of 1944, a small labor camp (Arbeitslager) was established by the Nazis in Spaichingen, a town near the Swiss border. The camp consisted of three barracks.

One of the prison barracks in Spaichingen after the war (KZ Gedenken Spaichingen)

The 300 to 400 prisoners transferred to Spaichingen worked at the local Metallwerke factory and on various construction sites. The Hungarian communists in the factory quickly established covert connections with German workers. János Eisner was assigned to work directly with one of the kapos (prisoner functionaries) as a kind of assistant kapo. With the help of his comrades, he managed to secure better tool and plate-making jobs for them. "The nationality group that was able to gain positions that gave it the ability to act and pull together was the one that survived. Those who went it alone were sooner or later destroyed," said one surviving communist, 23-year-old Árpád Jámbor (Dachau prisoner number 125104, Natzweiler number 38486), reflecting on the experience after the war. Jámbor’s words were not an exaggeration: death claimed many lives in Spaichingen.

Original plan of the Spaichingen camp and Metallwerke, 27 May 1944 (KZ Gedenken Spaichingen)

In March 1945, a Jewish labor serviceman, Sándor Klein, arrived in Spaichingen from Buchenwald with his companions and later provided a detailed account of the harsh conditions they endured. "The workplace was a horrific sight; we worked in knee-deep mud on a completely clayey floor. The pace of the work was further accelerated by the rubber batons of the kapos. We all looked like the living dead. After 12 hours of hard work each day, our rations consisted of 2 deciliters of bitter black coffee and 100 grams of bread in the morning, 3/4 litre of turnips thrown into warm water at noon, and more coffee and a piece of bread for dinner. Everyone's bodies were covered with bleeding sores from the lice."

The victims

With such conditions, it is no wonder that the prisoners soon began to die. The first Hungarian political prisoner, 25-year-old György Takács from Budapest, died on New Year's Eve 1944. He was followed on 9 January 1945 by 52-year-old Sándor Katona (born in Szeged, residing in the 10th district of Budapest) and 36-year-old Sándor Faludi (born in Budapest, prisoner number 126267 in Dachau, number 38457 in Natzweiler). The official cause of death for the latter was cardiac and circulatory failure (Herz-u. Kreislauversagen).

Árpád Jámbor later recalled the loss of his comrades as follows: "Then, at the end of January and February, András Dobozi, Gyula Ott, and János Bubán died from hunger. We had to witness the deaths of the Poles, Hungarian Gypsies, and the sons of other nations. One incident that remains etched in my mind is still vivid. On a Sunday, we were lined up in the yard, in the howling snowstorm, which, according to the SS, was for some fresh air. András Dobozi collapsed from the group. He could no longer stand and crawled on all fours toward the hospital barracks. Slowly, slowly, and halfway there, he died before our eyes. It was impossible to leave the line or offer help, as doing so would have been punishable by death by the SS."

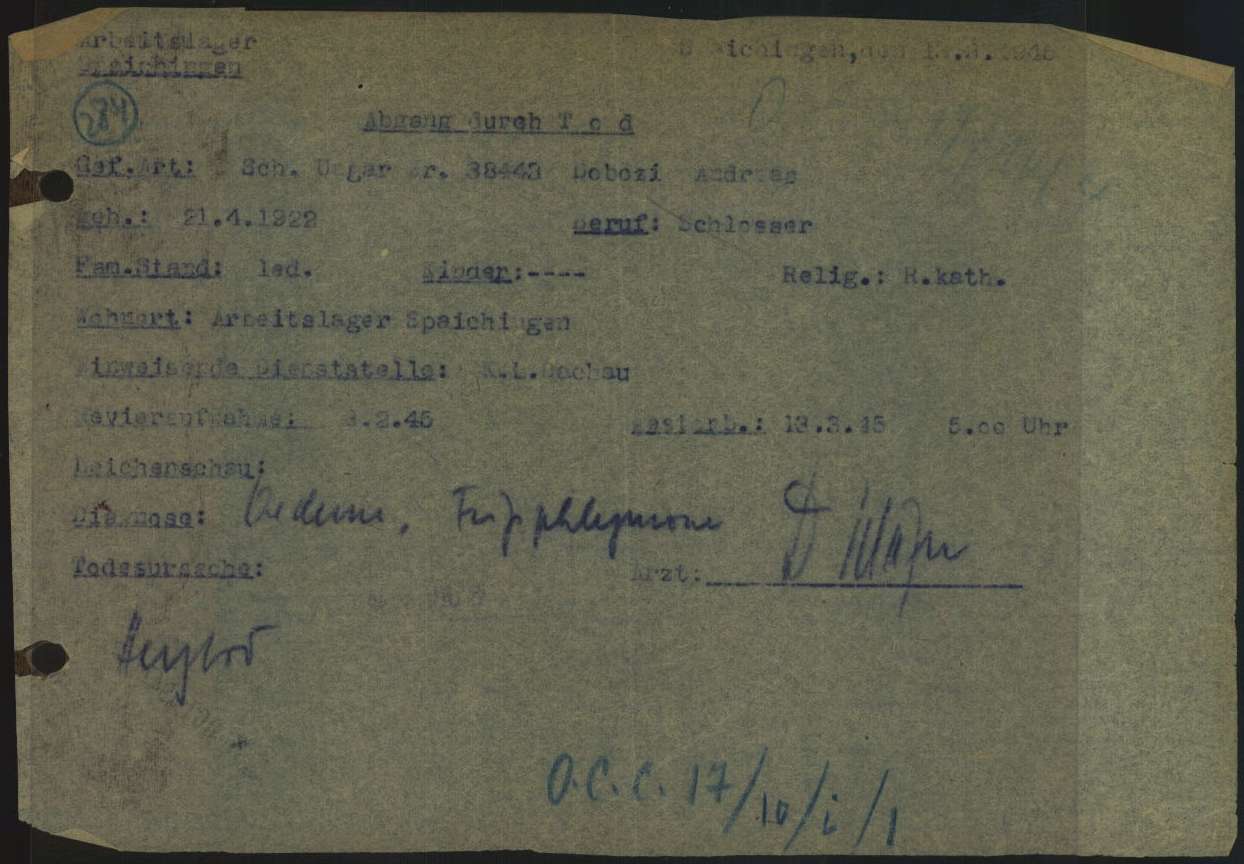

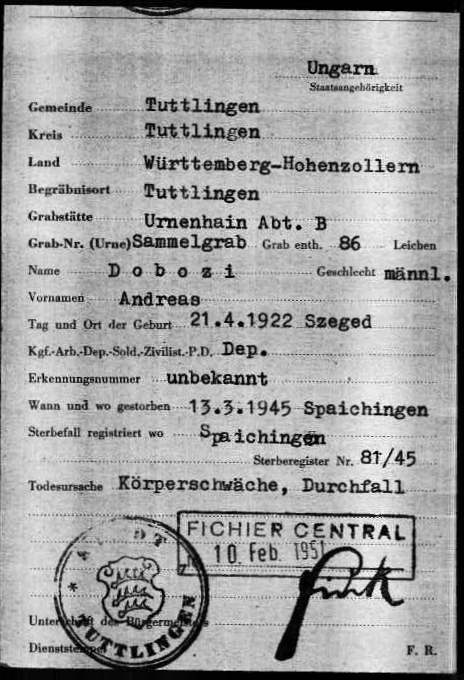

The Spaichingen record of the death of András Dobozi (Arolsen Archives ITS)

The surviving German documentation agrees with the account, except that most of the deaths occurred in March 1945. For example, 22-year-old university student András Dobozi died at 5 a.m. on 13 March 1945. According to the camp infirmary record, he had pus-filled abscesses, and his body was bloated from starvation (phlegmone, oedema). The cause of death was subsequently reported as physical weakness and diarrhea (Körperchwӓche, Durchfall).

Post-war document about András Dobozi (Arolsen Archives ITS)

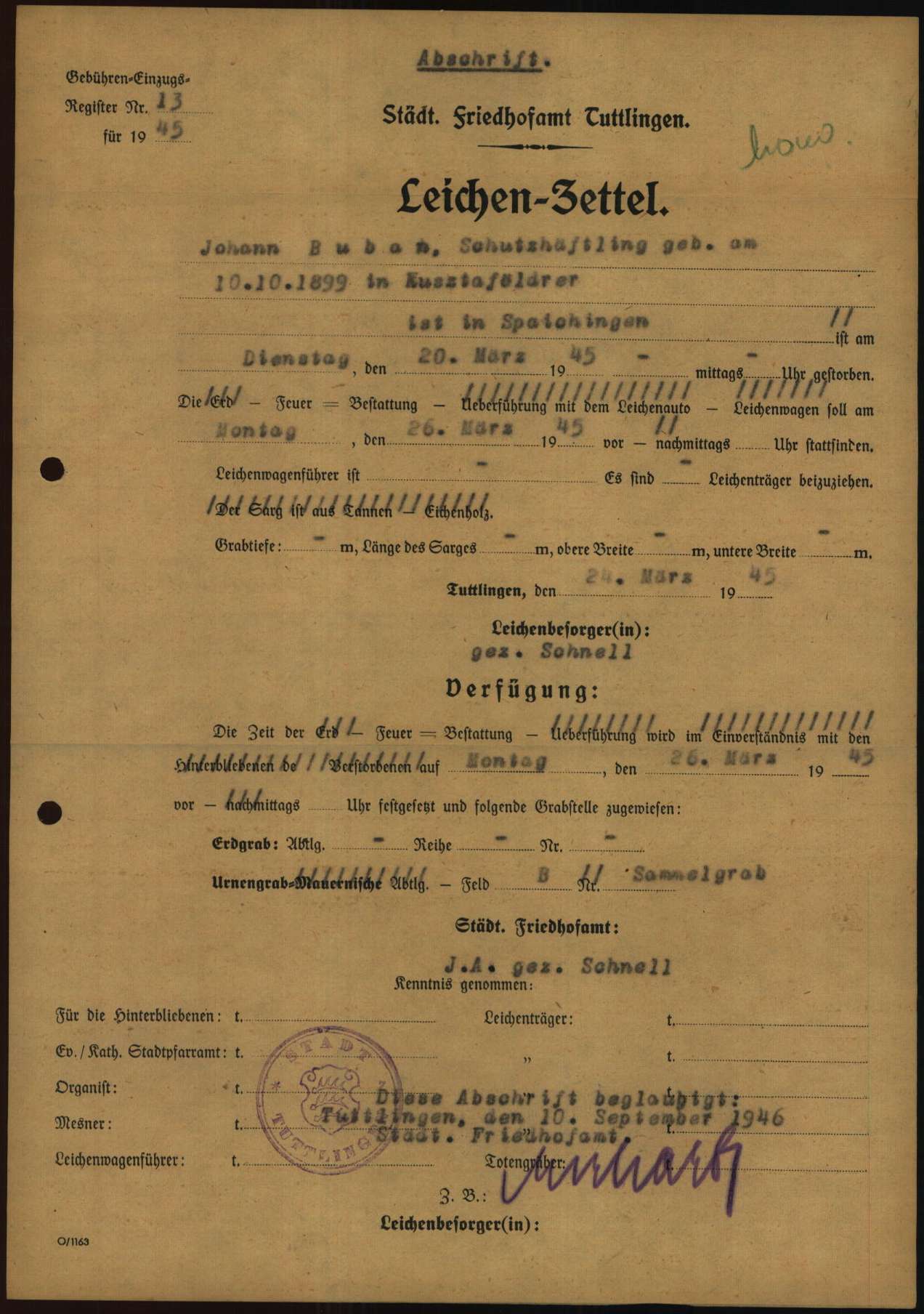

The 45-year-old János Bubán, born in Pusztaföldvár (prisoner number 125054 in Dachau, number 38426 in Natzweiler), mentioned in Jámbor’s recollection, was a bus driver before his arrest and also served as a secret radio operator for a group of resistance fighters in Budapest. He died on 20 March 1945. Gyula Ott, a 21-year-old laborer from Pestszenterzsébet (prisoner number 124952 in Dachau, Natzweiler number 38536), passed away on 29 March. The cause of death for Bubán was recorded as cardiac and circulatory weakness (Blut- und Kreislaufschwäche), while for Ott, it was noted as physical and cardiac weakness (Körper- und Herzschwäche).

In March 1945 alone, 16 Hungarian political prisoners died in Spaichingen. Within a few months of the subcamp's establishment, the mortality rate surged to 24-32 percent, a significant figure even by the standards of the Nazi camp system.

The death of János Bubán was also recorded in the registry office of the neighbouring town of Tuttlingen (Arolsen Archives ITS)

Death march, liberation

With the approach of the Western Front and the Allies, the evacuation of the subcamp began on 17-18 April 1945. "In the evening, the SS Kommandant announced that we would leave the camp and march on foot—likely to Dachau—and that anyone who could not keep up would be shot along the way. Four groups of 100 were formed, and I was in the first group. We set off, and after the first 5 kilometers, we were given a 2-minute rest. I was struggling to march and took off my shoes to keep up. Several of my comrades were shot along the way because they could not endure the march," recalled the aforementioned labor serviceman, Sándor Klein.

He escaped from the column in Wurmlingen one evening, taking advantage of the cover of darkness. German civilians helped him reach the town hall, where he was questioned by the deputy mayor, Eugen Müller, and a Catholic priest, called Hecht. Klein was in horrible state, his body weight was 32 kilograms. Müller and Hecht treated his wounds and hid him in a convent. A few days later, the French liberators arrived. Jámbor escaped from the death march in Spaichingen near Althausen with a Polish prisoner who spoke German. They, too, were hidden by Catholic nuns.

Upon returning to Spaichingen after liberation, Klein identified "two SS officers—who had been in the camp—two kapos, at whose hands approximately 95 people died. We managed to hand them over to the French, who took care of them. Additionally, several Nazis, whom I knew for certain were not innocent, were also delivered into the hands of the French." After liberation, Jámbor and his comrades joined a unit of Polish forced laborers and fought the SS under French leadership.

Role reversal after the war

Upon his return home, Árpád Jámbor rose to a high-ranking position in the communist secret police, the State Protection Authority (ÁVH), and later served in the State Security Services of the regime after 1956. In 1949, it was the ÁVH that arrested Lajos Lindenberger, the former prison commander who had prevented the execution of left-wing rebels in Sátoraljaújhely during the German occupation. Despite the testimony of the former rebels on behalf of their jailer, Lindenberger was tortured until he confessed that András Szalai, one of the accused in the showcase trial against former communist leader László Rajk, had been his informer in the prison.

Szalai was a communist of Jewish descent from Pécs. He was arrested by the right-wing regime in 1942. During his interrogation, investigators subjected him to such severe torture that he suffered brain injuries. In 1943, following another arrest, he was sent to Sátoraljaújhely prison, where he participated in the planning of the uprising. Just before the outbreak, he was permitted to leave prison for a medical examination, allowing him to survive the war underground. After 1945, he was given a prominent position in the communist party.

1949: András Szalai in the Rajk trial (Jewish Community of Pécs)

In 1949, the communist dictatorship sentenced to death the former Sátoraljaújhely prisoner, who had been imprisoned as a communist, as well as the former prison commander who had saved the surviving resistance fighters from German bullets after the uprising. Szalai was hanged, while Lindenberger died in prison before his execution.

In total, dozens of Sátoraljaújhely rebels perished in Nazi concentration camps. Some died in Dachau and Buchenwald, while others were killed in subcamps of Natzweiler, such as Spaichingen and Dautmergen.