Waves of Violence: Arrow Cross Terror in Budapest

October 15

“October 15, 1944, a bright and sunny Sunday. Someone rushed in, panting: Hungary had laid down its arms. I cannot describe what I felt. We ran out into the corridor, and the whole house was buzzing. A few people huddled together and ran to the gate to take down the star. But the happiness lasted only half an hour. An indescribable sense of uncertainty hung in the air. The radio played marches. It was unbearable. In the evening, we learned that Szálasi had become the head of government. It was over.” Hilda Löbl's lines from 1946 faithfully reflect the wide range of emotions—from euphoria to despair—that most Budapest Jews experienced on 15 October 1944, the day of the Arrow Cross takeover.

Militiamen on the day of the takeover at the Arrow Cross weapons depot at 10 Pasaréti Street, Budapest

The turn of events must have been particularly disheartening, as in the preceding weeks, the storm clouds had seemed to dissipate over the heads of the Jews in the capital. After being confined to so-called yellow star houses by the Hungarian authorities in June 1944, their deportation seemed imminent twice: once in early July and again at the end of August. But something always happened at the last minute. The first time was when head of state Miklós Horthy halted the deportations after months of watching his own authorities, with German assistance, deport the entire Jewish population of the countryside—some 440,000 people—to Auschwitz and other camps. Seven weeks later, at the end of August, the political and military situation changed radically when Romania broke with Berlin and sided with the Allies. From that point on, the Germans no longer pressed for the deportation of the remaining Hungarian Jews, so it was off the agenda. Horthy dismissed the collaborationist government led by Döme Sztójay, who had orchestrated the deportations, and set up a new, more moderate cabinet.

Since the beginning of September, the situation had eased noticeably. Some of the internment camps on the outskirts of the city were disbanded, the prison gates were opened, and many Budapest Jews were able to return to their families. As a special gesture, curfews were lifted during the major Jewish festivals in the autumn, allowing worshippers to go to their temples. Even the relentless propaganda of success could not conceal the fact that the Allied troops were advancing on all fronts. The defeat of the Germans, and with it, the salvation of the remaining Jews, was imminent.

Meanwhile, Horthy and his circle reached out to the Allies and began preparing to abandon the alliance with Germany. However, Berlin was aware of his every move. On October 15, Horthy announced his intention to negotiate an armistice with the Allies, but the Germans forcibly removed him from power and replaced him with Ferenc Szálasi, leader of the far-right Arrow Cross Party. Chaos erupted in the streets of Budapest.

The First Wave of Violence

Hastily armed Arrow Cross militias, often aided by German forces, immediately launched attacks on Jews. SS soldiers and Hungarian gunmen stormed 64 Csengery Street, for example. According to the testimony of a man who survived by pretending to be dead, "Children, women, men—21 people in total—were shot dead in the apartments in a completely arbitrary manner." Many others were killed in the Népszínház Street and Teleki Square areas.

On October 22, Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg reported that 100–200 people had been murdered in the first days. On October 19, Hungarian writer Miksa Fenyő recorded in his diary that the number of victims had already reached the hundreds. The day before, German envoy Edmund Veesenmayer had cabled Berlin, stating that "individual atrocities and murders against the Jews of Budapest are also on the agenda, which the new government intends to put an end to." His assessment was accurate; in an effort to consolidate power, the new regime reined in the armed groups after a few days. "No one should be an arbitrary or autocratic judge of the Jews, because it is up to the state to resolve this issue," declared Interior Minister Gábor Vajna in an appeal. "And this issue – rest assured – will be resolved."

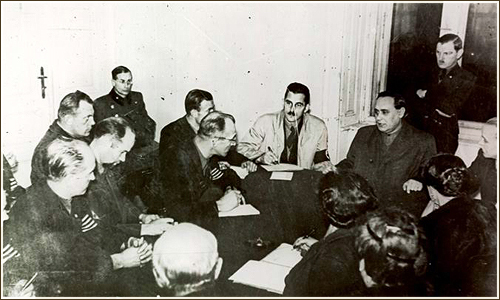

Ferenc Szálasi and the Arrow Cross general staff

Despite its confident rhetoric, the Arrow Cross regime’s policy toward the Jews was highly inconsistent. Initially, Szálasi opposed the resumption of deportations, but Interior Minister Gábor Vajna eventually agreed with the Germans to hand over 50,000 Jews. Although Vajna adamantly declared, "I do not recognize any kind of protective certificate or temporary passport," he was soon pressured by neutral embassies to acknowledge diplomatic protection, which was ultimately extended to tens of thousands of Jews. This issue quickly became the focal point of Szálasi's Jewish policy. Since his primary international objective was to gain official recognition for his regime, protests from neutral states carried significant weight. It was largely due to this that, after the deportation of tens of thousands of Jews, Szálasi halted further deportations—much to the Germans' frustration. The remaining Jews in the capital were concentrated into two ghettos between late November and early December. Those under diplomatic protection were moved into scattered apartment blocks in the southern part of Újlipótváros, between Margaret Bridge and Szent István Park. Those without valid or forged passports were crammed into a ghetto, enclosed by a palisade, in the area bordered by Dohány Street, Nagyatádi Szabó Street (now Kertész Street), Király Street, and Károly Boulevard.

The yellow star house at 28 Katona József Street in 1944. One of the buildings of the "international ghetto" in the winter of 1944/1945 as a Swiss protected house (Fortepan/Tivadar Lissák)

Terror at its peak

Between late October and the end of November, there was a slight decline in uncontrolled outbreaks of violence. This period saw the Szálasi government's deportation campaign, during which thousands of Jews were rounded up and forced to march on foot to the western border. Although violent incidents remained frequent, mass killings within the city limits decreased, as armed groups were primarily tasked with overseeing the deportations. This, to some extent, redirected the Arrow Cross militias' anti-Jewish aggression. The forced marches had already drawn international condemnation, and the Arrow Cross leadership likely sought to avoid further inflaming tensions by carrying out massacres in front of diplomats stationed in the capital.

However, in the six to eight weeks from late November until the fall of the Arrow Cross regime, terror gradually reached its peak. Several factors contributed to this escalation. The Szálasi government slowly came to realize that neutral states would not recognize its authority, weakening the protection offered by diplomatic immunity. In the final weeks, even diplomats’ lives were at risk. Just before Christmas, as Soviet and Romanian forces encircled the city, the government fled, leaving the Jews’s fate in the hands of local Arrow Cross leaders and militia commanders. Budapest became the site of one of the most devastating urban battles of the Second World War. In the fighting, 35,000 civilians, approximately 80,000 Soviet soldiers, and around 50,000 German and Hungarian troops were killed. Public order collapsed, and human life became increasingly expendable. As the city descended into bloody chaos, armed Arrow Cross groups grew even more radical. While they carefully avoided direct confrontation with the advancing Red Army, they intensified their murderous campaign against Jews with even greater brutality.

Robbery, torture, rape

The special Arrow Cross law enforcement unit, the “National Accountability Organization”, primarily targeted political prisoners and resistance fighters. Meanwhile, the Political Police Department of the Budapest Police Headquarters hunted down Jews in hiding and ordinary military personnel who deserted the collapsing Hungarian army. However, most people were not murdered by these agencies, but by members of the Arrow Cross Party and the armed “National Service”, both of which operated on a territorial basis. These units were largely composed of lower-level employees, workers, and members of the petty bourgeoisie who had joined the Arrow Cross in 1944. The majority were young or middle-aged men, though some women also took part in the atrocities. Among them was 23-year-old Lujza Háy, who burned naked Jewish women with cigarettes and beat them with leather belts at the Arrow Cross headquarters on Városház Street. Another known perpetrator was 45-year-old worker Etel Pap, who tortured prisoners at Nagyatádi Szabó Street.

The vast majority of the perpetrators joined the militias driven by the allure of robbery and the unchecked power over others. Until then, many had lived on the margins of society or within the lower strata of the semi-feudal, rigid system, with little hope of upward social mobility. With Szálasi's rise to power, the barriers that had once confined them suddenly dissolved: they were armed, empowered, and became masters of life and death. Mass rape is a tragic example of the brutal exercise of power and the outburst of this repressed frustration. The routine sexual violence perpetrated by Arrow Cross members was as much a part of their activities in Zugló (District XIV) as it was among the armed groups in District XII and other areas. Armed men patrolling the international ghetto in Újlipótváros often raped their victims in abandoned carriages at Western Railway Station. In some cases, they even assaulted young girls before shooting them into the Danube.

The Chain Bridge in 1944 seen from the Buda side. The riverbank on the opposite side was a favorite execution site for the Arrow Cross: Jews were shot en masse into the river from here (Fortepan/Tivadar Lissák)

The Arrow Cross terror in the capital bore only a faint resemblance to the industrial-scale extermination carried out in German death camps or the highly efficient bureaucratic machinery of the Horthy regime carrying out the mass deportations in the spring and summer of 1944. The Arrow Cross regime in Budapest was characterized by more or less random raids, chaotic executions, and victims who were sometimes arrested and then inexplicably released. Yet, extreme cruelty was a constant. The bodies of many victims were brought to the Forensic Medical Institute, where one of its staff members recalled: "The fewest were simply shot; most were horribly tortured. Most suffered for a long time, and from the gruesome contortions of their faces, you could tell that their suffering was excruciating. A bullet to the brain or heart was rare; the cruel traces of suffering were far more common. Their specialties were eye-shooting, skinning, disemboweling, and limb-breaking."

Although the Arrow Cross government attempted to curb the chaotic violence in the days following the coup, punishing the perpetrators was never considered. In fact, the new regime effectively defended its ruthless gunmen: the police investigations that had been launched were swiftly halted. Szálasi flatly denied that his party's agents had committed any atrocities, instead blaming the violence on "infiltrated extremist elements." In December 1944, in a bizarre twist of logic, Minister of Justice László Budinszky first threatened those spreading "slander" about the Arrow Cross murders, then added, "Thank God that there have been only this many victims in this revolution." It is telling that one of the Arrow Cross leaders in District XII, András Kun, a former Minorite monk, was not bothered while killing Jews. However, as soon as he began to act against army and police officers, he was arrested.

Arrow Cross Party servicemen, with András Kun in clerical garb on the left of the picture (Fortepan)

Between October 1944 and February 1945, the Arrow Cross carried out more than a hundred identifiable mass murders in Budapest, with the total number of victims surpassing five thousand.